It seems I have forgotten who I am, and in the forgetting, I have become ill.

Beyond my work as an author, writer, spiritual director, and educator, I have another job. For forty-nine weeks of the year, the job is fine – good even. Three weeks of the year, not so much – not because of the job itself, but because of the price to my nervous system. Being a highly sensitive empathic introvert who struggles with the symptoms of C-PTSD, Epstein Barr, kidney disease, and hypothyroid, I’m vulnerable on a normal day. During these three weeks, ones that require much more from me than usual, I find I struggle. To survive these three weeks, I find I only have the bandwidth to show up where I need to be, when I need to be there, and complete the tasks required. After the work is complete all I have left is to go home and “rot” (ie: disassociate, recover).

During those three weeks, I find it impossible to be my normal self. Instead, I find myself being short-tempered, impatient, grumpy, and extra sensitive. Whereas I have done a pretty good job of cultivating detachment and a sense of peaceful ease during normal weeks, for these three weeks – all bets are off.

I don’t like who I become when everything around me ends up being a trigger.

Following those three weeks, I spend as much time as possible doing nothing, hermiting in my cave, resting, sleeping, and trying to return to my so-called normal. A big part of this return to “normal” is trying to remember who I am when my nervous system isn’t being overstimulated by too much sound, vibration, movement, light, and other people’s energies.

Now that those three weeks are over, little by little, I’m starting to remember.

When a task takes so much of our physical, emotional, and mental effort, it is easy to forget who we are REALLY. Getting lost in to-do lists, unexpected emergencies, other people’s emotions, and all the details that go into a monumental creation, it is easy to forget that we are not those tasks. We are not the emergencies. Neither are we other people’s emotions. Even with time to regroup and recover, remembering who we really are beyond these responsibilities is difficult at best.

- Remembering requires separation. Separation and distance from what made us forget.

- Remembering demands quiet, stillness, and silence – asking us to enter into that place of calm where our true self resides.

- Remembering invites a return to routine – the routine out of which our body and soul feel nourished, safe, and supported.

- Remembering asks us to listen – to listen to the “still-small voice,” that knows our truth and what is important for our Soul’s fulfillment.

- Remembering is accomplished through practice – practicing the distance, the quiet, the routine, and the listening that support us in calling back all the strands of ourselves we have given away and then replanting them deep into the ground where they can begin (again) to thrive.

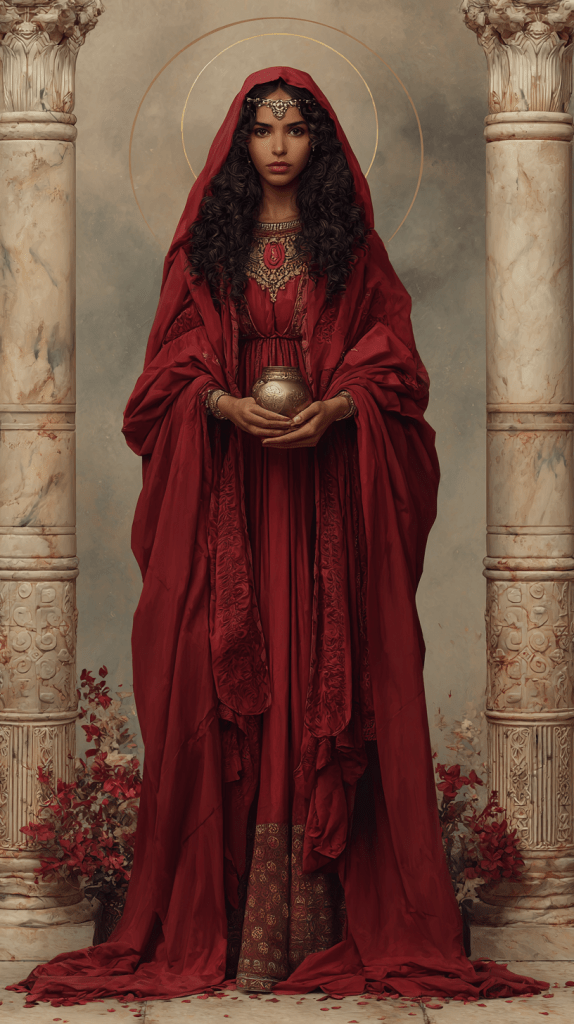

This year’s remembering has just begun, but already I’ve been reminded of why I’m really here. Not because of the tasks. Not because of the roles, certificates, or titles. Not because of what I do or how I make a living. I’m here to BE who I am and who I am meant to be and that has a specific symbol that has meaning only to me. If I share it, perhaps you’ll get a glimpse of the calling that will spark your own journey of remembering.

For nearly fifty years, (and many lifetimes), Lauri Ann Lumby has been a student and devote’ of Mary, called Magdalene. From original source material, Lauri has discovered remembered the secret teachings of Jesus, as they were revealed to the Magdalene. Lauri has applied these teachings in her own life and from this has developed a curriculum of practical study for those interested in remembering and embodying the truth of their original nature as Love.