Straight Talk About God Part II

Since the beginning of time, human beings have been creating God in their own image, not the other way around. In the earliest times, when humans lived close to the earth and whose survival depended on the whims of nature, it made sense that the first gods represented the movements of nature: storm gods, fire gods, water gods, all whose approval needed to be earned in order that humankind might survive. From this the evolution from nature gods to anthropomorphic deities resembling human beings in form and behavior was a natural progression.

Initially, these anthropomorphic beings were both male and female in form. At times they were primarily female as primitive human recognized that it was from woman that all humans come into being. Eventually, through events that can only be theorized, the feminine gods were supplanted by the male-only, all-powerful, warlike patriarchal god. This god, much like the nature gods, was one whose approval needed to be earned so that human beings might survive. For each human tribe, this man-god was given different names, but the qualities remained the same. Like human beings themselves, this god was jealous, vengeful, punitive, fickle, played favorites, and sometimes loved his creations. Mostly, however, this god needed to be worshiped, honored, and required sacrifice. Through “his” priests, this god delivered laws that required obedience. Straying from these laws elicited punishment, banishment from the tribe, and sometimes death.

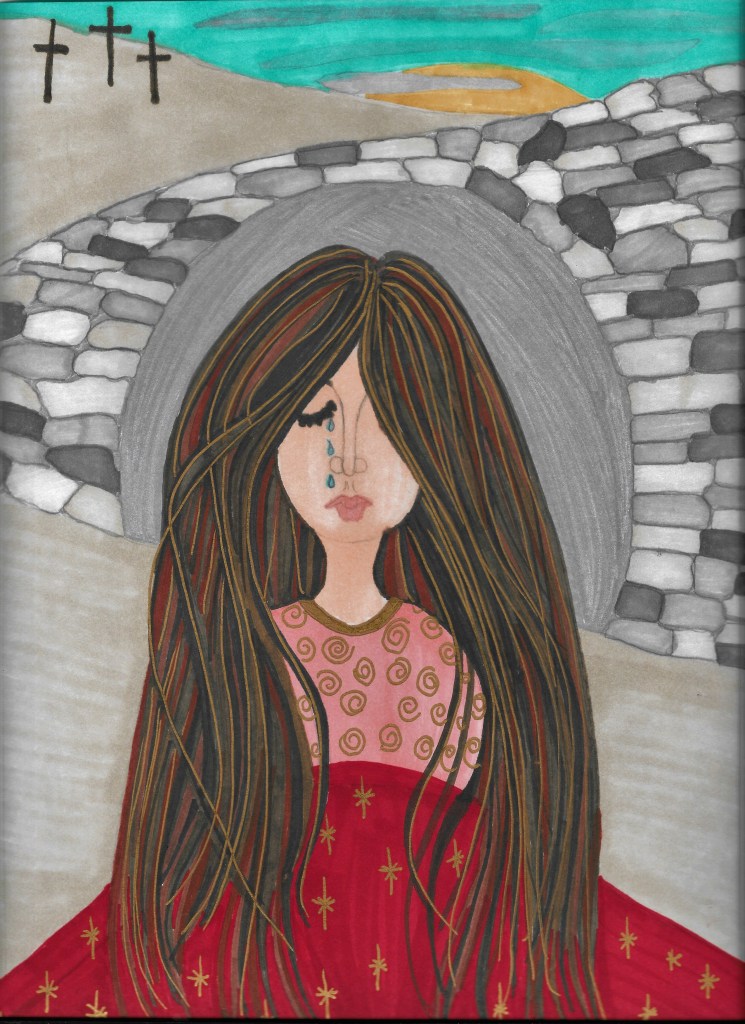

These human-made gods have not evolved much in the last ten thousand years – at least not in the way these gods are articulated in the context of institutional religion. “The Old Man in the Sky” god still holds sway. AND YET – while this is the god created by man, this is NOT the god experienced by the mystics, and certainly not the God that Jesus came to know and tried to describe to his companions. The god of the institution is one born out of the mind. The God experienced by mystics is one born of the heart. This is the God that Jesus said “dwelled within us” and the one we can come to know by “going into our inner room.” And yet, this God was not of Jesus’ experience alone. Mystics, contemplative, and holy people since the beginning of time have described the experience of knowing versus knowing the Divine, the emphasis placed on the former.

Through the mystics, humanity has been introduced to a God beyond the anthropomorphic god of humankind’s creation. The God that the mystics experienced was one that transcended material form and human behavior. There are no real words to describe this experience of God, though attempts have been made through such words as: Presence, Being, Essence, Transcendence, Enlightenment, Nirvana, Bliss, Ecstasy, Spirit, The Void, The No-Thing. The author of the epistles accredited to John, called this God Love.

In the Catholic church in which I was raised, the old man in the sky God was (and continues to be) the favored image of God, specifically, God the Father. God the Father is the source of all creation, the architect of the universe, omnipotent, omniscient, loving like a father, but also one whose judgment we were taught to fear. For the majority of Catholics this father-god (specifically male) is their sole image of God, and one they will defend in spite of the fullness of Church teaching.

But the Church itself teaches that God is not exclusively male. In fact, the official teaching of the Catholic church is that God has no gender and in no way resembles humankind:

“In no way is God in man’s image. He is neither man nor woman. God is pure spirit in which there is no place for the difference between sexes. (Paragraph 370 Catechism of the Catholic Church).”

I’m just going to leave that here for those raised Catholic to read again, and again, and again, as they/we attempt to reconcile this official teaching from what we were taught by our pastors, nuns, teachers, and parents.

God is pure spirit and in no way resembles humankind. BOOM!